Auditoria

The relationship between spectators and architecture is symbiotic – the social context shapes the architecture and the interior shapes the communal experience within it.

The arrangement of spectators within auditoria reveals the social organisation of the communities that use them. Social hierarchies are reproduced as the distinctions between the areas of seating or standing in these spaces. The freedom of movement between these areas suggests a wider rigidity or fluidity between social groupings based on economic class, ethnicity, caste, and gender.

Plans

All five theatres include auditorium design features that allow spectators to observe the reactions of their fellow spectators while watching the performance.

The curved tiers of seating, the dress circles and boxes, and the visibility of the auditorium floor from the upper levels of seating all encourage this degree of community engagement.

In four of the theatres, the auditorium remained lit. Spectators could see each other because the candle or gas-lit chandelier in the auditorium was needed to light the actors on the stage. Even in Stardust, which used electric lighting, the cabaret/dining arrangement required some light in the auditorium during the show.

Three Moments in Time

Three of our theatres mark moments when a venue was filled with spectators watching a specific performance.

We consider the Rose, Queen’s and Stardust as auditoria with a fixed demographic from a moment in the life cycle of the venue.

Who was there? Where were they sitting or standing?

The Rose on 2 October 1594 for Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus

The audience in the Rose Theatre showing the galleries (purple) and the pit (red). Model by Ortelia.

🟣 The Galleries cost two pennies. Gallery seating was unreserved; patrons moved around for better views or company. Better off patrons sat in these sheltered sections, as did chaperoned women.

🔴 The Pit at ground level cost a penny for standing room. Almost all Londoners could afford this charge, but these ‘groundlings’ came from all social strata.

The audience in the Rose Theatre showing the Lord’s Box (blue). Model by Ortelia.

🔵 The Lord’s Box above the stage was reserved for the upper echelons of society—those with titles. They paid sixpence. Their rank required the actors on stage to play to them with appropriate deference.

The Queen’s on 11 January 1841 for Shakespeare’s Othello

The audience in the Queen’s Theatre. Model by Ortelia.

🟠 Gallery – seated (orange) and 🟡 standing (yellow) – skilled workers, more men than women

🟢 Dress circle (green). Professional class and their families.

🔵 Boxes (blue). Professional and managerial class and families.

🟣 Pit standing room (purple). Unskilled men, with fewer women and children.

🔴 Pit seated (red). A mixture of skilled and unskilled workers (men and women, likely young), singles and families, children but not babies in arms.

Visualising the audience at the Queen’s

A painting of Proclamation Day in 1836 provides an image of the community at the time of occupation.

The Stardust from 4 July 1958 for the Lido de Paris

The Stardust made an affordable appeal to a broad audience across the mobile, mostly white, middle-classes of America.

The auditorium at the Stardust seated audience at tables in a restaurant formation. The table-tops nearest the performance were at the same height as the stage floor. Seating at tables further from the stage were elevated on tiers.

Admission to the Stardust showroom was nominally free, although there was a minimum charge per person of $3 for drinks.

Reservations for particular dates were taken and patrons may have been able to arrange seating at particular tables in advance.

Production costs were cross-subsidised by earnings from the gaming room.

Photographs taken during performance show the social relations of labour. Between the men and women seated in the audience and the artists performing on stage, we see the women employed to wait on the tables.

Audience configurations change over time

We compare the auditoria of two venues in which the demographics of the audience change over time.

The itinerant Cantonese opera form traveled over large distances around the Pacific Rim.

The Komediehuset was a fixed venue. Its interior was reconfigured throughout the nineteenth century and suggests the changing structures of the community.

粤剧 Yueju Cantonese Opera

In China, Cantonese opera entertained entire villages, and most performances were free as the community came together for a festival experience in the grounds of the temple.

A painting from the museum in Foshan illustrates the location of the community in and around the temple complex, eager to watch the opera. The major temple in Foshan included a fixed stage and surrounding galleries.

We can imagine that informal seating arrangements were put in place by the village or temple authorities for important spectators. The stronger spatial distinction in the audience is actually between the gods and humans.

These audience-performer relationships were maintained as Cantonese workers moved beyond China to locations around the Pacific Rim.

A Chinese opera stage near the former Ellenborough Market, Singapore, 1890s, photo: National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

The crush of migrant labourers eager to watch Cantonese opera in Singapore provides a sense of the popularity of the form, as well as its community backing.

This photograph appears to be a largely male audience of workers, probably part of the migrant/indentured workforce flowing into Singapore between 1823-1891. They worked in mines, ports, plantations, construction sites, rickshaw pullers. Since such labour was intended to be short term before a return to China, women tended not to travel.

The cartoon offers a sense of the many thousands of Chinese labourers arriving on Victorian goldfield sites such as the etching of Ballarat. Their interest in some recreation and a reminder of home would have been great; travelling Cantonese Opera companies, such as Fook Shing’s company, filled this gap.

Melbourne, 1872: Lee Goon’s company performs in their tent on the site of a burnt out theatre. We have duplicated the single line of audience in this image to create the sense of a full house.

Lee Goon’s tent theatre performance, Melbourne, 1872. Samuel Calvert and Oswald Rose Campbell, ‘Chinese Theatricals in Melbourne’. Courtesy of State Library Victoria.

Komediehuset

The auditorium of Komediehuset changed multiple times during the life of the theatre as it shifted from an amateur venue, to the home of resident professional companies, and finally to a cinema and hall for hire.

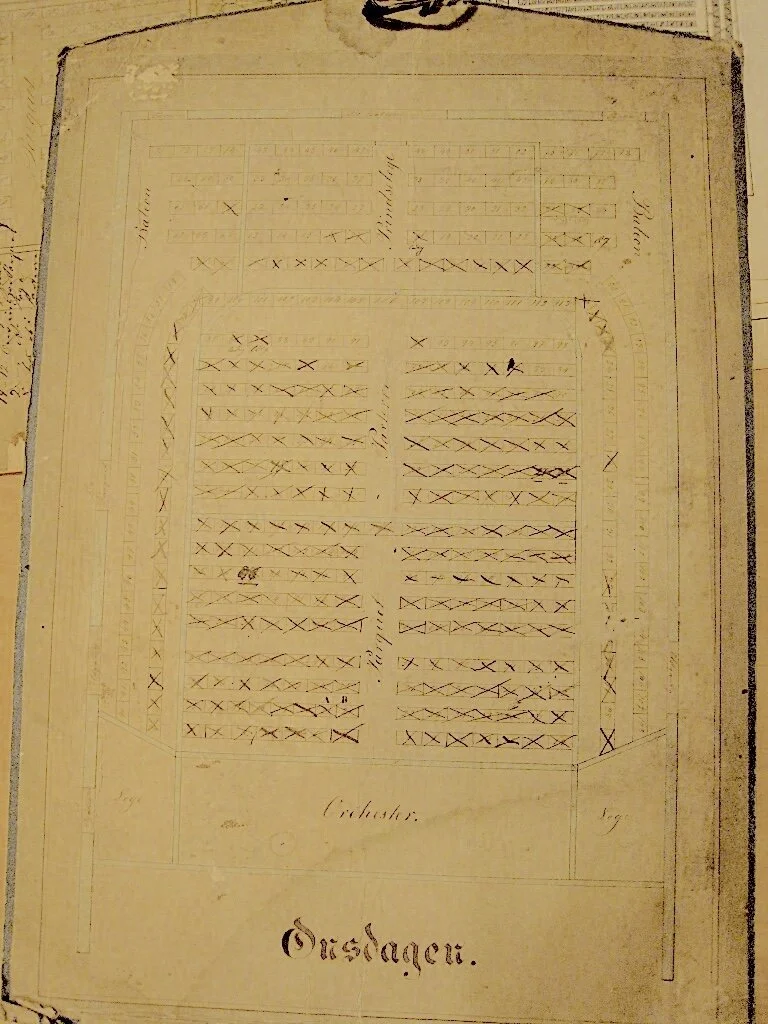

Box office seating plans for Komediehuset show changes in the auditorium during 1850s.

First change in 1856 for visiting Princes… established a larger box in the balcony.

Although the terms parterre and parquet are used on these early plans, the French terminology is reversed with the latter being closer to the stage.

Interior of Komediehuset model showing 1850s auditorium. Courtesy of Ortelia.

In the 1850s, the audience came from all sectors of society: the wealthy merchant class, the emergent middle class of office workers, teachers, and public servants, and the growing working class. Usually the audience was divided into two groups: the Wednesday night subscribers and the Sunday night general public.

In the 1870s, the auditorium was reconfigured. The architect, Peter Andreas Blix, provided the Board of the Theatre with alternative designs. They chose the modest proposal which focused on the curving of the gallery into a dress circle, while adopting the ornate designs for the circle façade and the auditorium ceiling from the more lavish design. This auditorium remained unchanged into the twentieth century when the theatre was used as a cinema.

Audience in Komediehuset taken in the early twentieth century. Courtesy of The Theatre Archives, Section for Special Collections, Bergen University Library.

A theatre never completed…

The Blix auditorium design that was rejected by the Board of the Theatre as too expensive was based on French theatres that echoed the anatomical structure of the human eye. The auditorium sightlines in this architectural conceit follow the logic of vision, with the forestage curved in the shape of the cornea and the circular seating creating the back of an eye from which the stage spectacle could be seen from multiple perspectives.

Proposed fly tower and new dome roof above stage. Architectural Drawing by Peter Andreas Blix. Courtesy of The Theatre Archives, Section for Special Collections, Bergen University Library.