One of many such forms in China, 粤剧 yueju, also referred to as Cantonese opera, relies on well-known narratives, arias, and character types. This sung form (with the musicians present on stage) spread throughout southeast Asia, as this 1909 company photograph of the Qing Wei Xin Troupe in Singapore illustrates.

Qing Wei Xin Troupe, Singapore, c. 1909; Qing Wei Xin (庆维新) is also transliterated Heng Wai Sun. (Collection of Part Woh Woi Koon, Wayang: A History of Chinese Opera in Singapore, Singapore: National Archives, 1988, pp. 36-37).

The venue has changed significantly over time.

It was originally performed very simply in a temporary bamboo theatre constructed in the grounds of a temple.

Postcard of a bamboo theatre in Chinatown near the Singapore River, 1900 (National Archives of Singapore, Wayang: A History of Chinese Opera in Singapore, Singapore: National Archives, 1988, p. 23; also at China Postcard, Flickr).

The scale of these bamboo venues has grown significantly through the twentieth century.

Model of a Theatre being made from bamboo, with the help of bamboo scaffolding. Hong Kong Heritage Museum (photo: authors).

This short clip illustrates a bamboo theatre being built into a tight, sloped space in front of a small temple (next to the Cathedral) in Macau.

Construction of a bamboo theatre, Macau, 2018 (video: authors).

Today in Hong Kong, Macau, or southeast China, Cantonese opera might be performed in a pop-up large-scale bamboo venue like this, with more regular, ticketed seating or in a permanent indoor proscenium arch venue.

Bamboo theatre for Cantonese opera, Hong Kong (BBC, 2013).

These images of 彩鳳鳴劇團 Choi Fung Ming theatre troupe performing at Lei Yue Mun, Hong Kong, in 2018, illustrate the simple backdrop and props that support the elaborate, codified costumes and make-up that characterised Cantonese opera in its earlier forms. In the twentieth century the form often adopted more elaborate staging but this example adheres to the historical conventions.

彩鳳鳴劇團 Choi Fung Ming theatre troupe at Lei Yue Mun, Hong Kong, 2018; thank you to Theresa Wang (photo: the authors).

Bamboo theatre stages were usually positioned next to a temple.

Tai Shang Temple, Foshan

Tai Shang Temple in Foshan (photo: authors).

The traditional location for Cantonese opera is facing or adjacent to a temple so that the gods can watch the performance. The temple we used as a typical temple style is Tai Shang Temple (1665) in Foshan, used today as a memorial for martial artist Zhang Hongsheng (1824-1899).

Tai Shang Temple in Foshan (photo: authors).

The Tai Shang Temple in Foshan is now in a heavily built-up area and is now used by a martial arts group. In its original use, this type of temple would have accommodated temporary Cantonese opera troupes in front of or next door to it. The colocation of the theatre with the temple was important because theatre was, first and foremost, an entertainment for the gods who had the best view of the action.

Large scale temples also exist, but in the smaller scale style, the key architectural elements are clearer.

This is Guangzhou Sanyuanli Pingyingtuan Yizhi: this temple illustrates the relationship to the joss house in Australia.

Guangzhou Sanyuanli Pingyingtuan Yizhi (photo: authors).

Gods

Gods were part of the theatre itself as well as the nearby temple.

This is Master Huaguang, one of the gods worshipped by Cantonese opera artists, typically found backstage in theatres and on red boats. Hong Kong Heritage Museum (photo: authors).

Temple gods at Tai Shang Temple, Foshan (photo: authors).

A larger temple could accommodate a theatre inside its walls.

This model, in the Hong Kong Heritage Museum, depicts a stage with the temple structure in the foreground (photo: authors).

The first performance by a troupe of Cantonese opera artists is a ritual performance for the gods. This is a ritual performance at Wan Fu Stage, Foshan, China (photo courtesy of Li Wanxia from Foshan Ancestral Temple Museum).

Troupes

This is the Guan Di temple in Foshan. Note the ‘pot ear’ roof architecture that is typical in Foshan, and reproduced in Tai Shang Temple as well.

Guan Di temple in Foshan (photo: authors).

The river location is typical, given that opera troupes travelled from temple to temple by water. They used what became known as red boats, two per troupe. They lived and trained on these boats. (photo: authors)

Model of a red boat, Ghangzhou Museum of Cantonese Opera, Foshan (photo: authors).

A model of a red boat from the Guangdong Museum of Cantonese Opera. No boats remain.

The tight accommodations on the boats were mirrored backstage. These specific storage and dressing facilities are replicated in Australian Cantonese performances as well. These images provide an indication of backstage conventions although they are from the more recent iterations of the tradition.

Goldfields

Trade opportunities took Chinese labourers to numerous locations through southeast Asia while the lure of finding gold in Australia, New Zealand, US, Canada, and Peru took labourers even further from home.

A Chinese opera stage near the former Ellenborough Market, Singapore, 1890s, photo: National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

“Transnational Routes of Cantonese Opera via Steamship and Railway Lines, ca. 1890-1914.” © April Liu, 2019; from April Liu, Divine Threads: The Visual and Material Culture of Cantonese Opera (Vancouver: Figure 1 Publishing, 2019), p. 4. Liu’s map is based on studies by Donna R. Gabaccia and Dick Hoerder (2011), Zou Shishen and Zheng Ningen (2008), and Nancy Rao (2017), and historical maps by George Philip (1914) and John Bartholomlew (1891).

Conditions in Australia were difficult for all labourers and particularly for the Chinese who faced heavy discrimination. They sought familiar entertainment which they readily found but not in bamboo theatres.

Albert Charles Cooke, ‘Chinese Quarter, Ballarat’, State Library Victoria.

The traditional temples, known in Australia as joss houses, were recreated in mining camps, in smaller form, and often in a more temporary form, since the miners had every intention of making money and returning to China.

Joss houses (temples) were simple buildings, usually wooden, that were designed to suit the needs of the Chinese community for their sojourn in Australia. Few miners intended to stay and so few joss houses suggest permanence.

Joss House, Bright, Victoria. Courtesy of Stephen McCall.

Guan Di Temple, Queen Victoria Art Gallery at Royal Park, Launceston (photo: authors).

Nevertheless, some have remained such as this example, Guan Di Joss House from Weldborough, a tin mining community in northeastern Tasmania. Dating from the 1880s, it was preserved when the Chinese population in the community dwindled. Once decommissioned, it was moved into the Queen Victoria Art Gallery in Launceston as a permanent exhibit.

Guan Di Joss House, Weldborough, Tasmania, 1880s (video: authors).

The building material of choice in Victorian goldfield settlements was the canvas tent: it was durable, readily available, and portable.

Circus-style tents were used for multiple purposes, including Cantonese opera performances. Yet the tent was modified to reproduce the same configuration that the bamboo theatre offered, rather than the form being heavily modified to suit its different surroundings.

Ashton’s British-American Circus in Clermont, Peak Downs in 1873 (Australian Town and Country Journal, 3 May 1873: 17; reproduced in Mark St Leon, Circus: The Australian Story, Melbourne Books, 2011).

Model

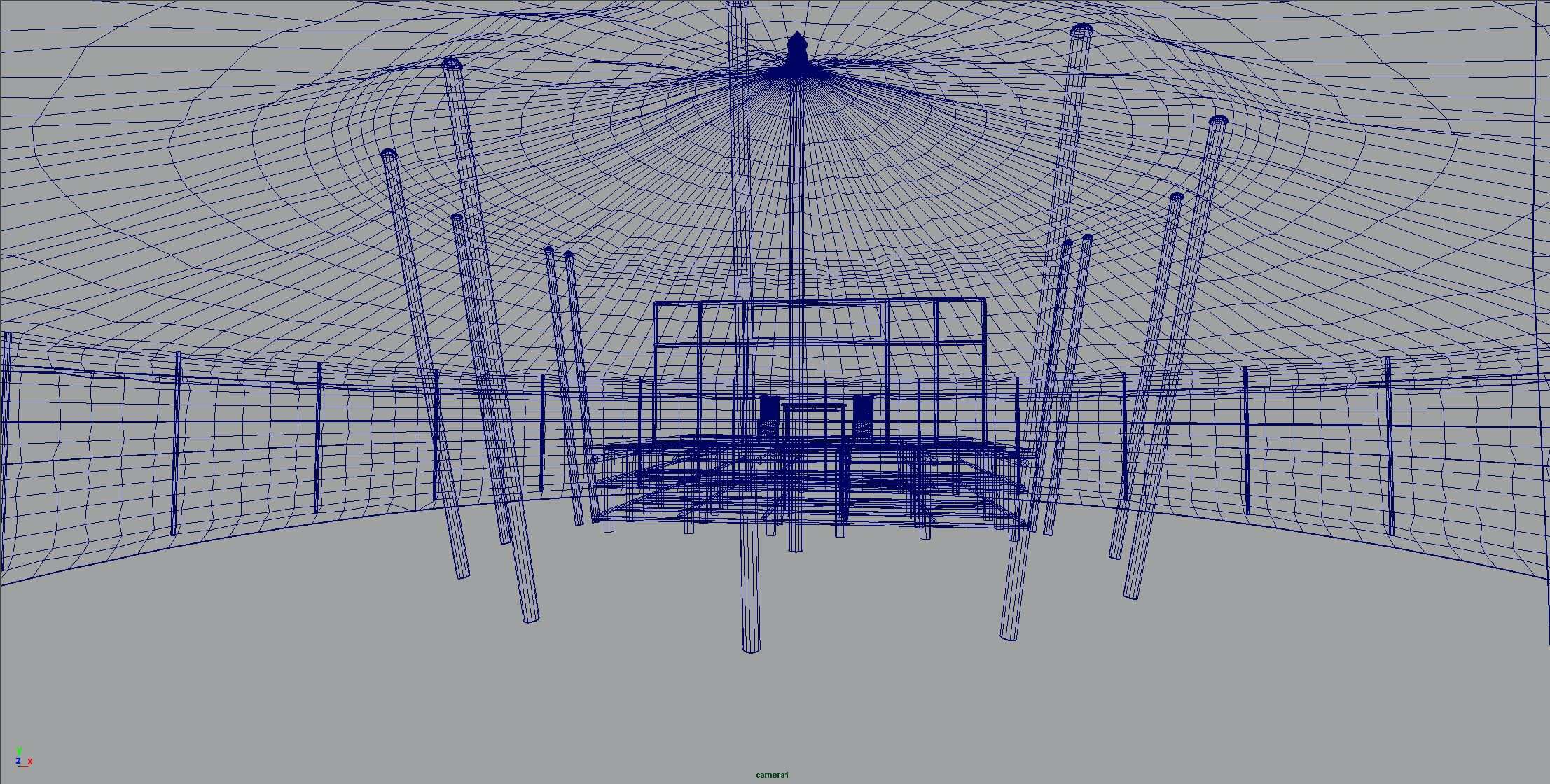

This screen shot illustrates the same simple platform from the bamboo stage replicated inside a circular canvas tent. The name of the company is displayed in traditional Chinese characters at the top: 福盛劇團 Fook Shing Theatre Company.

A version of this paper cut image surrounds the temple in the virtual model to suggest a conflation of the Australian goldfields with the Guangdong region of China, via Cantonese opera.

Paper cut image, typical of the Foshan region, by Master Chen Yongcai.

The video fly-through of the VR model shows the Cantonese opera stage inside the circular canvas tent on the Victorian goldfields and a bamboo theatre and temple from Foshan.

The tent for performing Cantonese opera in the Victorian goldfields (1850s and 1860s) is based on the dimensions of Fook Shing's tent. The bamboo theatre and the temple are based on actual constructions at the time in the Foshan region of China.